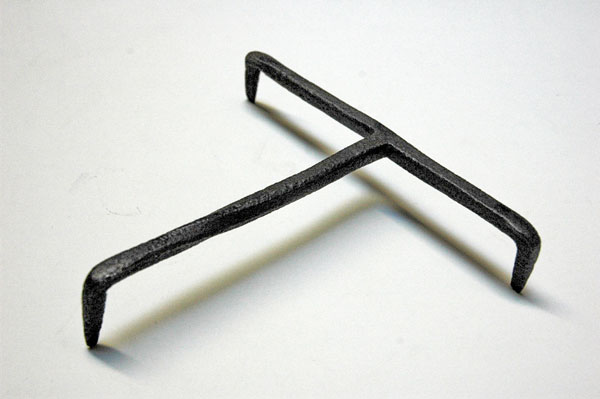

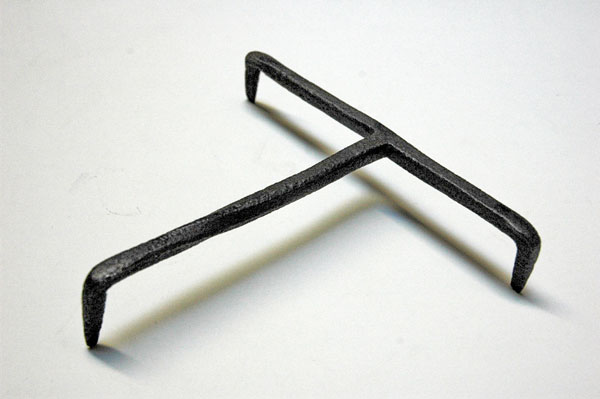

wrought iron trivet, likely late eighteenth century, probably Rhode Island 7" x 5.75" x 1.75"

I'm normally almost dysfunctional if asked to speak in front of a group, but I hardly hesitated when Austin Thomas asked if I would be a part of “One Image, One Minute: Significant People Present Significant Images”. The event, hosted at Hyperallergic on June 22, was a benefit for Camp Pocket Utopia, a creative summer project, social school and free arts camp for kids, being put together by Thomas and the nonprofit space Norte Maar. Their ambitious program, to be located at Rouses Point in upstate New York, will be based on a learning model created at Black Mountain College, as interpreted by Thomas, who describes it further:

The Camp hopes to inspire a conversation amongst artists, creative thinkers, and the community, empowering participants and observers to think for themselves while offering a free arts camp for the kids of Rouses Point, NY, and the surrounding North Country.

I was honored, and eventually psyched (almost) to be a part of the terrific "show and tell" organized as a fundraiser for the project. Thomas had asked twenty-five people to each submit an image of something very important to them, and to talk about it for one minute. Almost immediately I thought of the trivet shown at the top of this post, and told her I would contribute, since I knew I wouldn't have any trouble talking about something I know well and which has meant a lot to me.

I only had to stand up there for 60 seconds. How hard could that be? It turned out that the hardest part was the time restriction. I didn't want to read from notes, and I didn't want to stress out by doing too much preparation, but, less than an hour before leaving for Williamsburg, when I first did a run-through, I realized I had enough material for five or ten times my time slot.

We were told we would be called up in alphabetical order, so I had plenty of time while I waited. Grade school flashback: Once again Wagner was going to be the last to give his report (I'd like to think Austin had thought of that conceit, for its connection to her larger, school-ish project). I managed to pare it down a lot from my piece while I sat waiting my turn, but much of the story survived.

It was a successful experiment. It made for a thought-provoking evening, and it drew a great group of people - on both sides of the tiny apron stage.

One of the reasons the trivet had come to my mind must have been that it was a simple and beautiful thing. It was a rough material, yet it had left the forge with an awesome grace. It was totally functional, but perfectly sculpted: Each of its branches was chamfered along its entire length and the 90-degree twist of the longest arm was an artist's aesthetic gesture and, perhaps, a strengthening fillip.

It was also a thing whose description, and even its personal importance, I originally thought could be described in one minute.

In spite of, or perhaps because of, my enthusiasm for contemporary visual art, It had not occurred to me to look there for a subject. The reservoir was too vast, and I probably sensed that I'd never be able to focus on the one work which, using the adjective in Austin's invitation, was particularly "important to me". I had looked elsewhere for my subject.

For many years I had created, and still cherish, an environment pretty much removed from modernism of any kind. I chose to share something from that world; I chose this trivet, a humble piece of worked ("wrought") iron.

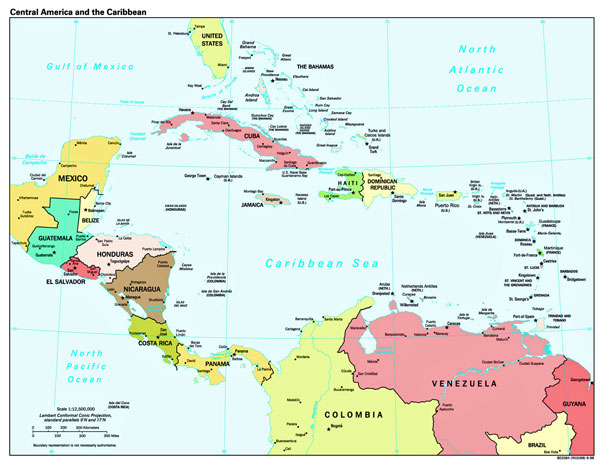

It was created in southeastern New England, probably somewhere in Rhode Island, and probably in the late eighteenth century. Its working purpose: to elevate a plate, pan or heavy pot above hot coals spread onto a hearth, or, alternatively, above a table surface which would be damaged by a hot vessel.

The material is bog iron, which was once found locally near the surface of the ground (no longer of any practical interest except to antiquarians). It's a very low-carbon metal (unlike steel), and easily malleable. It was the work of a skilled blacksmith. It has a characteristic "grain" (again, unlike steel). Because of its purity, it's extremely resistant to rusting.

I brought it with me from Rhode Island 25 years ago, when I decided to give up the simple mid-eighteenth-century clapboard house in Providence which I and my partner at the time had bought (in 1970). We restored it [I have to say, "lovingly" restored it] over a number of years, until it looked like it had never needed restoring. It was both a home and a house museum: I thought we would live there until we died, and it was furnished entirely with things appropriate to its date, its geography and the particular economic circumstances of its original occupants. There was essentially no upholstered furniture.

This trivet was a working part of that house, and so was I.

The curatorial assignment my partner and I had undertaken (after we learned the real antiquity of what we had initially thought was just an old rundown house, a very rundown house) precluded living with contemporary art, in spite of the interest we both had for the art of our own time. Instead, for 15 years I lived with art that was contemporary to the earliest period of the house, and there was very little of that.

In the years of assembling things for the house I consciously avoided interesting examples of regional New England folk art, even though it wouldn't have been difficult to secure such things, because it seemed so unlikely that the interior of our very modest, and genuinely urban, house would have seen much of the folksy kind of decoration so prized today. Also, Shaker design did not yet exist at the time the house was built, and when it did, the communities which produced it were nowhere near Rhode Island. Much of what I did have may have looked "Shaker", but I can't say any of it was.

But I kept my passion for both historic and contemporary art, even if I was sheltered under a very old roof and beside a large, fully-equipped cooking hearth. Beyond my newly-founded antiquarian interests, I still wanted to be surrounded by art. The house itself was an incredibly understated design, and I found myself going for the simplest, most elegant forms of practical furniture and artifacts, in wood, glass, metal and pottery: There was that fabulous Mochaware mug with a geometric shape and pattern which would not have looked out of place in the Bauhaus, and that beautiful provincial Sheraton side chair with squared, vertical splats, that could have posed as a Josef Hoffman prototype.

I did some serious cooking in that house, in both the almost-modern kitchen and on the open hearth (I cook more than ever today, but without those wood fires), so I'm not surprised that I almost immediately fell in love with the small tool which I had picked up, probably in an old barn, soon after we were first able to use the fireplaces.

My partner and I broke up, and when I finally decided to decamp to New York, in 1985, I sold much of its contents and put the house up for sale.

I brought the trivet with me. Today it rests only on the counter or the table. Its cooking days may be over, but I prize it as much as I ever did, for its function, its beauty and its associations. Although there are hundreds of drawings and paintings hanging on our walls, when guests are here, especially for dinner, I'm just as likely to pull this little black tripod off the kitchen counter and play "show and tell" with it as anything else in the apartment.

So is it sculpture? I seems to defy categories. Although it may end up on the table at many meals, while the pot it supports will return to the kitchen, the trivet remains. I never tire of looking at it.

The other presenters at the benefit were Laura Braslow, Deborah Brown, Paul D'Agostino, Anna D'Agrosa, Jen Dalton, Kianga Ellis, Louise Fishman, Veken Gueyikian, Rachel Gugelberger, Chris Harding, Valerie Hegarty, Roger Hodge, Lars Kremer, Ellen Letcher, Matthew Miller, Brooke Moyse, Ellie Murphy, James Panero, Gravelle Pierre, Cathy Nan Quinlan, Paul Rome, Adam Simon, Jonathan Stevenson, and Douglas Utter.

[someday soon I hope to set up a gallery devoted specifically to images of the house]