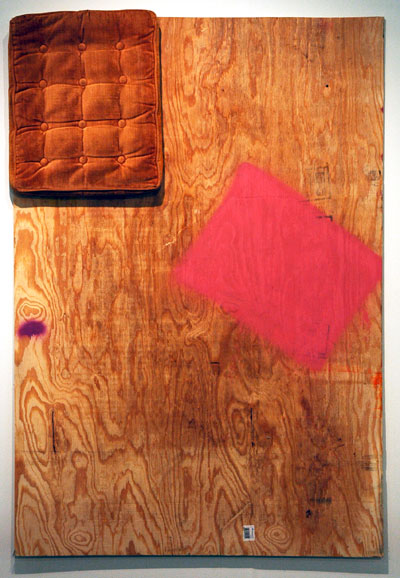

untitled ("feather-light") 2009

It's an even more awesome and happy sight when they're seen moving.

untitled ("feather-light") 2009

It's an even more awesome and happy sight when they're seen moving.

Republic Windows employees celebrate getting everything they asked for, after sit-in

taking over the factory

After writing up my report of what was said by others at last Thursday's panel at the X Initiative I asked myself what I thought about the question implied in the program's title: "After the Deluge?; Perspectives on Challenging Times in the Art World". I've decided to continue the discussion I had with myself in this space.

As far as the economy is concerned, I think things are going to get pretty crazy out there, and they may perhaps stay pretty crazy for a long time. In spite of the optimism coming from Washington and in much of the press in the last few days, I still think we're sliding into another great depression. I'd say they've really broken it this time. I'm especially concerned because I'm not hearing anyone who is supposedly in charge really admit it.

If the U.S. population is a little more than 300 million and the total amount of the so-called bailouts and capital infusions remains no more than the estimate of $9.9 trillion published in an article in the Times two months ago (which now may seem a very optimistic assumption), those numbers equate to more than $32,000. for every single American. And yet it may not do the trick. The country, and the whole world, might still collapse into chaos.

Under both best- and the worst-case scenarios, there will be changes in the way we all live.

But let's put aside the doomsday bugbear; it seems there's something else going on, and this phenomenon just might turn out to be a good thing. People are not just worse off than they were one year ago, or perhaps eight or even thirty years ago, as we're now learning. People are mad; they're *really* mad; and it's not just about the AIG bonuses. It's about the selfishness, the greed, the arrogance and the pure stupidity of those who have been given those bonuses, as well as all the other financial tycoons, and their fellow-traveling politicians too. They have together created the disaster which is taking from people their jobs, their savings and their hopes, while mortgaging their future and that of their children with the trillions of dollars stuffed into the pockets of those same tycoons and politicians, in transactions which remain opaque today.

For what it's worth, we can be sure this debacle won't look anything like the last one. When things like wars and depressions come back, when historical things are repeated, they actually never do "come back", and they really never are "repeated". World War II looked nothing like its almost-equally infamous namesake. We can also be sure that Great Depression II will end up looking nothing like the first one, which seemed to have defined the 20th century almost as much as totalitarianism, genocide and industrial progress.

One thing we do know is that nothing was ever quite the same both during and after the Great Depression. I think there's a good chance that nothing will survive the current crisis in the same form in which it existed just one year ago, including the current arrangements within the art world. I have no predictions about galleries or other institutions, but the relationship between the artist, the gallery and the public may be altered. It's probably safe to assume that while some will certainly survive and eventually flourish once again, any space which today we think of as on the leading edge will almost certainly be supplanted in that role by others not yet in business, and the old edge will become the middle ground.

But assuming we don't end up tearing each other apart over scraps of food, maybe we can look forward to "interesting times" as for artists and the people who love them and what they do. I've assembled a far-from-exhaustive list of developments which I think we're likely to see just ahead of us, if not already. It does not include trends which would seem to be unrelated to the economic depression, like digital experimentation. Also, most are not entirely new concepts or developments, and some of them are already here.

Every artist will finally get a website, including those who have held out because of some idea of principle, and those who have depended on their galleries.

There will be more virtual art, meaning both online work and projects.

We will see an growing trend toward the adoption of "open source, open content and open distribution" (pace Eyebeam).

There will be more interactive work.

Individual artists and groups of artists will be showing work in their studios, art both by themselves and by others.

Artists will organize shows themselves in vacant buildings and storefronts, even if private and public institutions fail to do so.

Some businesses, large and small, will find it useful and rewarding to cooperate with artists in a symbiotic relationship.

A distressed economy will encourage the recognition of the folly, and even counterproductive consequences, of camera prohibitions.

We can expect to see a greater popular documentation of the visual arts, where it doesn't interfere with its appreciation by others.

We will see more street art and more street performance, both in more inspired forms than ever.

We are sure to see more work that reflects the growing populism abroad in the land today.

And consequently, we will see more socially and politically provocative work (actually, that may be mostly wishful thinking).

But this new art will be subversive (no, I mean really subversive), even if it's not "Political".

There will be work which would have been unrecognizable as art, by most people, until now.

And certainly there will be art created in totally new mediums.

But, because of reduced budgets, we can still expect more works on paper and more work using found materials.

Governments and citizens will finally grant artists a status withheld from them until now, recognition as a full and worthy part of society in every way.

It all sounds good to me, but the best thing I've heard or read describing the positive things which lie ahead for artists even in our reduced economic circumstances was a piece Holland Cotter wrote for the Times, published February 12, "The Boom Is Over. Long Live the Art!":

At the same time, if the example of past crises holds true, artists can also take over the factory, make the art industry their own. Collectively and individually they can customize the machinery, alter the modes of distribution, adjust the rate of production to allow for organic growth, for shifts in purpose and direction. They can daydream and concentrate. They can make nothing for a while, or make something and make it wrong, and fail in peace, and start again.

Now if we can all just get through this no-money thing and crawl out the other side in one piece.

[image by E. Jason Wambsgans from the Times via Chicago Tribune and AP]

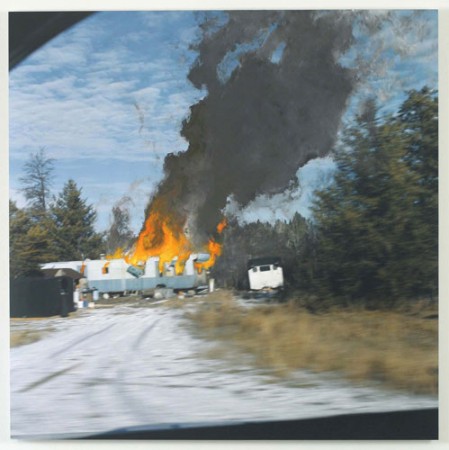

Rob Fischer Highway 71 No. 3 2004-2005 painted photograph

thoughts of living in reduced circumstances

Last night in Chelsea the X Initiative (actually, the "initiative" of Elizabeth Dee) hosted what was billed as a "town hall meeting and panel discussion", under the somewhat compelling rubric, "After the Deluge?; Perspectives on Challenging Times in the Art World".

It was a galvanizing evening, its importance having first been established by the economic developments of the past year, then furthered by the choice of the panel, and finally recognized by the fact that the seating was oversubscribed with art world people of every description. Virtually everyone in the audience was completely silent and apparently attentive during the discussion. It was very skillfully moderated by Lindsay Pollock, an author and a journalist with Bloomberg News. She's a star - and a nimble one at that: During the Q&A which followed Pollock fielded queries which had arrived on her computer during the presentation in the form of both emails and twitter (a first in my experience), and later fielded questions sent by low-tech upraised hand voice (inevitably the least audible of the three media, and so presenting perhaps a foretoken for the future of settings like this).

The panel was made up of a fairly narrowly-focused selection of occupations (gallerists, or artist/gallerists, and administrators), although there was certainly diversification within this small group. It included Jeffrey Deitch of Deitch Projects; Brett Littman Executive Director of The Drawing Center; Michael Rush, Director of the Rose Art Museum; and Anya Kielar, an artist and co-founder of Guild & Greyshkul.

I don't have most of the questions with which the moderator started the conversations on the panel. They were lost somewhere in that large, crowded room, having never made it to the small notepad balanced on my knee - in the dark. I was lucky enough to manage some more-or-less-legible scribbles which paraphrase portions of the answers, or statements. What follows are essentially my notes converted into sentences.

I think Pollock's first question was a general one, about the state of the art world today. Jeffrey Deitch began by saying that for many people the madness of the bullish art market had resulted in more than a little confusion in distinguishing between the most expensive art and the art which is most valuable.

He noted that museum curators had stopped visiting galleries and were instead buying art from the art fairs, and that Miami Basel was only the most dramatic example. And they were buying it straight off the walls. The traditional approach had virtually disappeared, that of visiting the galleries and then returning for the artist's next show, and sometimes visiting studios and talking to the artist, all of it to develop an understanding of and conversation with the art.

There had been what he called a "distortion" in the market, Deitch admitted, because of the extraordinary power of "the six billionaires" who in recent years actually were, the market [bear in mind that this was only at the very top end]. He quickly added that the number six was not a total exaggeration, and said that the most dramatic change within these exclusive precincts is the fact that this market has all but disappeared: He cited the collector François Pinault, who last fall cancelled every purchase he had made, all the way back to the previous April, as only the most dramatic example of this transformation.

He responded to something someone had said about the difficulty galleries have in a depressed market with the counsel that, "like any business", you have to live through both up and down periods. [here I thought to myself that it was easier to live through both if your ups were very up indeed].

I was actually surprised that as a hugely successful owner of three New York gallery spaces Deitch had taken the time to be a part of this discussion, and I was a little moved to hear his reply to a question Pollock asked later in the program: "What will change?" Deitch began, "We have our community", adding with great emphasis that it is a remarkable community. "We are going to use our community as an asset." He made analogies to the fraternity created in the last depression [my phrasing] by the WPA, which brought artists together who might never have known each other, or seen each other's work. He added that he believed the 1980 Times Square Show* was of similar importance for New York specifically, and that it became the foundation for the 1980's arts community.

In the Q&A part of the evening someone asked from the floor what the panel thought about calling for a new WPA. I didn't hear everything said in response, but there appeared to be little enthusiasm. Maybe it was only because it seemed like such a preposterous an idea to present to Americans today.

Barry had tweeted during the panelists' remarks, addressing to no one member in particular a question which he and I have both often discussed. It's related to a concept which had first excited me before I had even moved to New York in 1985. I'm referring to Creative Time's exciting early programs which put art into vacant storefronts and neglected landmarks, beginning with Art on the Beach in the late 70's. We can do it again.

Deitch took the question and sounded enthusiastic about the idea (well, sort of making it his own). He told a story about walking through streets in Soho with a friend from Beirut who, noticing all the empty stores, asked why the city didn't do something about it, adding that in Lebanon the government arranges to have art installed in such places. He thought it should be done.

[We absolutely should be doing this already. We have experienced people in place in several institutions now who could act as administrators and curators. We're going to have a lot of vacant stores for a while; artists never have enough spaces to show work; and most people never see enough art. It might have been a bit of a hard sell twenty-five or thirty years ago but today real estate owners and developers should jump on the idea. Art is now taken more seriously, and capitalism, well, it's not. I worked as a liability underwriter when I moved here, and it was clear to me that the biggest obstacle for these installations would always be the difficulty and expense of getting insurance to cover property owners who might otherwise be supportive. It still is. By the way, one of my company's biggest competitors, AIG, was always the most aggressive underwriter for this kind of odd risk arrangement. But New York City self-insures; there's no reason why it's not in the interest of the whole regional economy to absorb the risk for these minimal exposures. The idea is to turn the visual and performing arts, already integral to both the soul and the pocketbook of all New Yorkers, into an even more vital, attractive and economically-valuable part of New York (maybe the most successful part economically), at least until the rest of the economy can be reconstructed.]

Anya Kielar, who, with her two artist partners, closed the already-well-mourned Guild & Greyshkul space in February after five years, explained that they had done so only at the point they realized that if they were to pay the next light bill they would risk not being able to pay their artists. They had no capital, and no credit cards, and that's how they had always wanted it. Investors were interested in helping to continue, but they knew they would inevitably lose their independence with such an arrangement. Kielar also said that the decision was made easier knowing that running a gallery was not the only thing any of them had on their own.

Later in the evening she said that although she was fortunate to have success with her own work almost from the moment she left Columbia, she appreciates her teachers advising students early on not to rely entirely on their art. In fact, like many artists, she has been able to use her MFA to earn money teaching, even if her own assignment with a Bard program, teaching at Bayview womens' prison (in the Chelsea gallery district) might not be as financially rewarding as some. Speaking for her own relationship to the gallery system, she said that she was not currently associated with any, adding that independence had the positive aspect of enabling her to "flex and do projects". She suggested that artists shouldn't get too comfortable with a gallery anyway; galleries change, as artists change, and sometimes it's good to move on.

Kielar said that while she was there the art school structure had become and remains something of a community for her, adding "You don't realize that's one of the most important parts of being in school".

In the open part of the evening there was a short exchange related to her discussion of the teaching option. It started with someone's question about what effect the economic depression might have on school art faculties. It was suggested that we can easily imagine fewer art students in the foreseeable future and that would mean fewer teachers will be needed and fewer artists will be able to realize an income teaching, or even use small appointments to supplement other income.

People seemed particularly glued to Michael Rush's remarks, and not just because he happens to be the beleaguered director of the the Rose Art Museum**, and so represents, personally and professionally so much of what brought all these people to 22nd Street last night. He was impressive: articulate, gentle and humane.

I don't have a direct quote, but this is a pretty good description of how he started out: When the market was good, people said that art was all about money; now that the market stinks, people say it's all about money. He suggested we just leave money out of it, that we should be able to rise above money. He said that the experience of the last year or so (including his own, since learning that his museum's days were numbered) should teach us lessons of leadership and, . . . (hesitating for emphasis) humanity. He said he had learned not to let let panic determine action and how not to deal with other human beings.

He was emphatic that among the practical consequences of what Brandeis has already done will be that donors will, and should, ensure that more conditions are attached to their donations. He added that the days of "good faith" transactions are definitely over. Asking, "What is the public trust?", Rush said he wanted to make it clear that what was happening in Waltham was not about "deaccession", conduct in which a museum might properly engage under proper circumstances and for the right reasons. "This is about [a museum] selling art for money", and he argued that it was an enormously harmful and destructive development in the way we regard art, and that it must not be tolerated.

Brett Littman said that he believed one of the positive sides to the market downturn would be that for students leaving the academy the pressures to produce, or to conform to others' expectations will be lessened, that the environment for art will be "purified".

At the end of the program and before questions from the floor Littman, who is the executive director of the Drawing Center, had the last word when the panel was asked for predictions of what "changing times in the art world" will mean. Referring to the new reality, in a depressed market, of unaffordable materials and projects, he said, "I do think that it means artists will draw more".

The last questioner rose from the audience to ask the panelists how a constrained market was affecting the kind of art that is actually being made. She recalled that in the 70's, with OPEC raising oil prices, dramatic inflation in the cost of living, and the Vietnam war and its aftermath, we saw the growth of body art, performance art and conceptual art. Art seemed no longer to be about "making objects that could be bought or sold". I didn't hear any predictions from the table.

She suggested that the question might be the topic of the next town hall meeting.

It wasn't long into the evening's discussions that I was thinking myself how remarkable an assembly this was, and that it should somehow continue. Perhaps it might be in a different format and perhaps where it might be easier to make it more interactive - without keeping invited the guests up too late, or driving too many people crazy. Next time I'll even help with the chairs. Okay, I missed the GLF and the GAA, but I did ACT UP. Although real lives were at stake in that community of free spirits, it was also a swell fraternity/sorority.

NOTE: S.C. Squibb has a smoother, more concise account on the ArtCat zine.

*

Jerry Saltz, describing the show:

Young artists, critics, and curators begin their takeover of the New York art world with the "Times Square Show," curated by artists, and held in a two-floor former bus depot and massage parlor off Times Square. It included work by unknowns Jenny Holzer, David Hammons, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, Kiki Smith, Walter Robinson and many others who were making a loose street-wise non-academic, non-post-minimal art. The show is a call to artists everywhere to do what they want as often and as energetically as possible.

**

It was the Rose Art Museum, part of Brandeis University, which made the news two months ago when it was learned that the university's philistine administration had decided that the easiest way to make up their own endowment gap was to close the museum and sell all the art (in the midst of a major depression in the art market). The Rose itself is independent in its funding, has experienced no financial problems, and in fact passes on 15% of the money it raises directly to Brandeis.

[image from re-title]

What with everyone trying to show off their best things at once, it's always difficult to "cover a larger art fair - even physically - and Armory 2009 was no exception. I'll have to go back, but in the meantime what follows are images of just a few of the things that attracted my attention at the "Contemporary" section during last night's reception.

Richard Tuttle paper-pulp edition at Dieu Donne (new York)

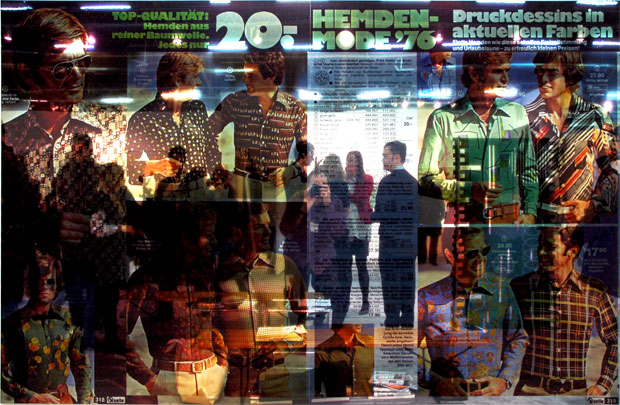

Josephine Meckseper print on reflective Mylar at Elizabeth Dee (New York)

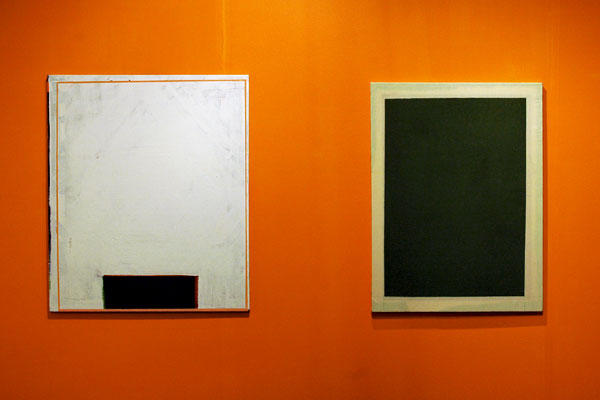

two David Godbold paintings at Kerlin (Dublin)

section of one Matt Connors wall at CANADA (New York)

two Gerwald Rockenschaub sculptures at Georg Kargel (Vienna)

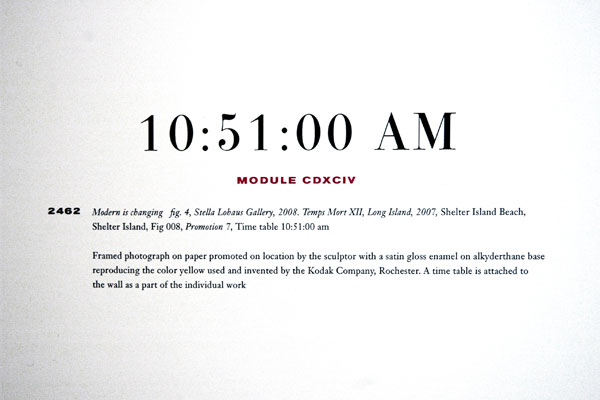

Jan De Cock architecture-related sculpture, including artist-countenanced reflections, at Stella Lohaus (Antwerp)

[large detail of artist's label]

Sarah Braman sculpture at Museum 52 (New York, London)

large detail of Fabian Marcaccio sculpture at Thaddeus Ropac (Salzburg, Paris)

small Merlin James acrylic at Kerlin (Dublin)

stroller spotted parked inside a booth during last night's VIP reception

untitled (two pots) 2009

It was only noon today, but I wanted to capture an image for the blog of the ho-hum big storm of March, 2009. At the same time, not wishing to suit up for the cold and the wet before breakfast, I decided to stick my camera out of the breakfast room window. It was still snowing.

Believe it or not, this is actually a color image: I can't wait until spring.

he's not just preaching to the choir

Billy's the real thing.

Reverend Billy of the Church of Not Shopping is more than a performer and a performance. His, its, their dedicated and vocal supporters are only one center of a contemporary activist, grass-roots movement for economic justice, environmental protection, and anti-militarism, but their performances and meetings have typically been among the most entertaining and joyful manifestations of a growing movement which may be about to come into its own, even if it may not yet be in sight of the promised land.

Bill Talen (Reverend Billy is the stage name he's used for years) wants to be mayor. Let me go on record right now by saying I'd vote for him at the drop of a hat, and that's what I saw happen today at noon in Union Square. Since the good Reverend himself is never seen in anything resembling a hat (his thick theatrical comb-back "do" probably supplies enough warmth), if I'm going to resurrect another hoary expression to describe what I saw, I'll have to emphasize that Talen threw his hat into the ring only metaphorically, when he declared his very serious candidacy for the office of Mayor of the City of New York on the Green Party Ticket.

If you've heard him speak you know Billy's a master with metaphor, but you may not know that he's a master at gently but firmly cutting through the cant, stupidity and obfuscation which passes for political discussion in New York. He's quick on his feet in front of both large and small crowds, but he reveals an awesome, genuinely-sincere mind - and heart - in the very smallest groups, or in one-on-one conversation.

He's an impressive speaker and an impressive candidate. If only he were able to appear in front of voters and speak to them as I've heard him talk, both in and, at least as importantly, out of his theatrical character, I believe he'd be a shoe-in for the office (another clothing metaphor, but we do know Billy wears shoes). They'll come to smile and to laugh, but the message he delivers is serious, and it now has more meaning for more New Yorkers than ever before.

In the midst of an economic disaster Billy can no longer be dismissed as a voice crying aloud in the wilderness, but of course for many of us he never was.

He's not going to be quiet, and as the candidate of an established party he can't be ignored.

When the choir had finished and he was done speaking, Talen walked down the steps from the rostra (where he stood at a white-painted wooden church "pulpit" constructed for an earlier "Church" action) to take questions from the press assembled below it. He was asked what he thought about the difficulty in beating the incumbent, Michael Bloomberg (the richest man in Gotham, who literally bought the office - twice - and is willing to do so again) "Bloomberg? I don't think he'll win; he's running against democracy; it's Mike vs. democracy, and democracy will win. It actually is that simple and clear to lots of New Yorkers". Asked if he himself represented democracy, he answered generously: "There are a number of very worthy candidates," adding, "we have to respect the people of New York", alluding at least partly to the voters' decision to impose and uphold term limits recently scrapped by the Mayor and City Council.

The new Green Party nominee pointed to the historic focus of his political activism up until now, New York's 500 real neighborhoods*, as the new political reality with which he will be working, and which he said should and would replace that of the paternalistic and undemocratic system of failed corporations, insolvent banks and ruined developers. "The key is in the neighborhoods, [even if] for some neighborhoods it's too late." Reminding us of one the Church of Not Shopping's battles, that focused on the multiplication of the big chains and the disappearance of local businesses, the Reverend seemed to be warning Bloomberg and the beneficiaries of his largesse, "We all now know what the monoculture is, and we know to oppose it."

From the candidate's letter to New Yorkers which appears on the campaign web site:

The 500 neighborhoods of New York, if they are healthy, are protecting our families and jobs. Local economies anchored by independent shops and public spaces are not as sexy to this administration as luxury boxes, corporate jets and the like, but really the greatness of this city is in its neighborhoods.

This would all sound like only an utopian dream if we weren't already experiencing the beginnings, within the country as a whole, of virtually a revolution in public attitudes and government programs proposed, and even an alteration in the political system itself, all being driven by circumstances, the internet, and Barack Obama's emergence originally as candidate and now as President.

ADDENDUM: Video documentation of the scene in Union Square yesterday:

Billy's oration

Billy and the press

Bill of Rights chorale

*

Billy says he and the members actually got together to try counting, and stopped at 500.