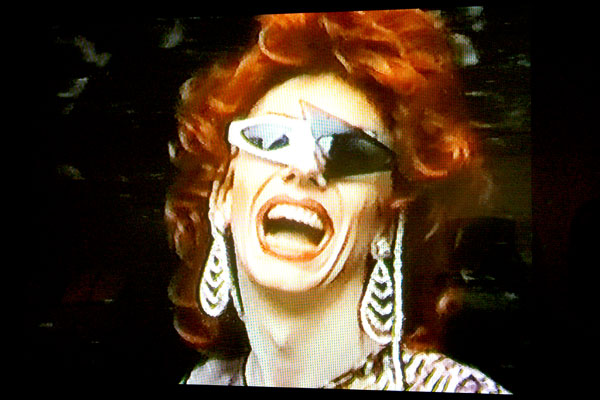

[four stills from the video installation of the film, "Captured"]

How do you write about a chronicler with a soul? How do you write about a bard with a camera? We can't begin to understand the importance of people like this until they are gone. Maybe it has to wait until we are gone as well, but in the meantime we can give it a try.

I'd have to see this show, "The Lower East Side", for its historical and political importance, even if the photographs didn't have their own beauty. And they do.

Clayton Patterson (okay, it's already the legendary Clayton Patterson) is currently represented by some of his sculpture, a tiny sampling of his enormous archive of photographs, and an excerpt from a documentary video in a show at Kinz, Tillou + Feigen, a gallery whose heritage, through Richard L. Feigen and Feigen Contemporary is itself pretty legendary.

The sculptures assembled from found materials are documents themselves, setting the entire installation in a specific time and space. The photographs are intense portraits, both candid and posed, of the Lower East Side community stretching from the early 80's to the present. To anyone who did not know this city before the mid-90's, or who might be unfamiliar with the neighborhood now, many will look like they must have been invented. In fact they are all perfectly true, and astonishingly intimate.

The same must be said of a film, "Captured", shown on a television monitor in the smaller space. Its subject is Patterson and the neighborhood he calls home and which he has looked after for almost three decades. It was put together by Dan Levin, Ben Solomon and Jenner Furst, largely using Patterson's own footage, and excerpts are being played in the gallery through the duration of the show. Patterson's photographs can be seen on the gallery site. Here I'm only showing stills from the film, except for this one image:

.jpg)

Clayton Patterson Untitled (grunge girl) 1992/2007 C-print

By the way, if you're very young, on the street, and want to have a distinctive style, wouldn't it make sense to find your own? That's why I was struck by the resemblance between this 1992 "Grunge Girl" captured by Patterson, and this 2002 "Billy", who was part of Bradley McCallum and Jacqueline Tarry's show at Marvelli gallery three years ago (the couple is now represented by Caren Golden).

[image at the bottom from ktfgallery]