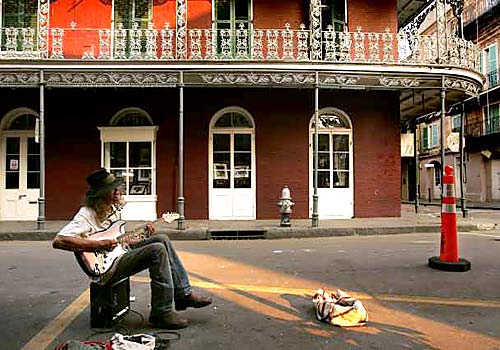

Troy Tallent brings some blues back to the French Quarter, by playing for the few residents and police still in the neighborhood. Originally from Georgia, Troy came to New Orleans in 1987 and he hasn't left yet. [Los Angeles Times caption dated September 3]

HELP AT HAND: Nita LaGarde, 105, leaves New Orleans convention center with her nurses granddaughter Tanisha Blevin, 5. Before coming to the shelter, they huddled in an attic and on an interstate island. Helicopters evacuated the elderly, infirm and infants. About 1,000 people remain. [Los Angeles Times dated September 4]

I'm publishing a second letter from Jordan Flaherty this morning, once again copied in its entirety. The first section includes his thoughts on the the city, the second is in the form of a diary and the third is the beginnings of a prospectus for aiding the people of New Orleans.

DON'T LET NEW ORLEANS DIEby Jordan Flaherty

August 27 - September 3, 2005

Its been a day since I evacuated from New Orleans, my

home, the city I love. Today I saw Governor

Blanco proudly speak of troops coming in with orders

to shoot to kill. Is she trying to help New

Orleans, or has she declared war?I feel like the world isnt seeing the truth about the

city I love. People outside know about Jazz Fest

and Bourbon Street and beads, and now they know about

looters and armed gangs and helicopter

rescue.What's missing is the story of a city and people who

have created a culture of liberation and

resistance. A city where people have stood up against

centuries of racism and white supremacy.

This is the city where in 1892 Homer Plessy and the

Citizens Committee planned the direct action

that brought the first (unsuccessful) legal challenge

to the doctrine of Separate but Equal. This is

the city where in 1970 the New Orleans Black Panthers

held off the police from the desire housing

projects, and also formed one of the nations first

Black Panther chapters in prison. Where in 2005

teens at Frederick Douglas High School, one of the

most impoverished schools in the US, formed a

student activist group called Teens With Attitude to

fight for educational justice, and canvassed their

community to develop true community ownership of their

school.I didnt really understand community until I moved to

New Orleans. Secondlines, the new orleans

tradition of roving street parties with a brass band,

began as a form of community insurance, and are

still used to benefit those needing aid. New Orleans

is a place where someone always wants to feed

you.Instead of demonizing this community, instead of

mistreating them and shooting them and stranding

them in refugee camps and displacing them across the

southern US, we need to give our love and

support to this community in their hour of crisis, and

then we need to let them lead the redevelopment

of New Orleans. As Naomi Klein has already pointed

out, the rebuilding money that will come in

doesnt belong to the Red Cross or FEMA or Homeland

Security, the money belongs to the people of

New Orleans.

HURRICANE DIARY

Many people have asked for more information about my

experience in the past week. I was one of

the fortunate ones. I had food and water and a solid

home. Below are notes from my week in the

disaster that was constructed out of greed, corruption

and neglect.Saturday, August 27

Im in New Orleans, and theres word of a hurricane

approaching. I dont consider leaving. Why?

Because I dont have a car, and all the airlines and

car rental companies are sold out. Because the

last two hurricanes were false alarms, despite the

shrill and vacuous media alarms. Because I have

a sturdy, second floor apartment, food, water,

flashlights, and supplies. Because there is not much

of an evacuation plan. Friends of mine who evacuated

last time sat in their cars, moving 50 miles in 12

hours.Sunday, August 28

As the storm approaches and grows larger, everyone I

know is calling. Are you staying or going?

where are you staying? Are you bringing your pets?

What should I do? Governor Blanco urges us

to pray the hurricane down to a level 2.I relent to pressure somewhat and relocate to a more

sturdy location, an apartment complex built out

of an old can factory in the midcity neighborhood.

The building is five stories high, built of concrete

and brick. There are seven of us in the apartment,

with four cats.Monday, August 29

Its morning, the storm is over, and we survey the

streets outside. There has been some flooding. A

few of us explore the neighborhood in boats, and we

see extensive damage, but overall we feel as if

New Orleans has once again escaped fate.Later in the day, we hear some reports of much greater

flooding in destruction in the ninth ward and

lower ninth ward neighborhoods, New Orleans most

overexploited communities.Tomorrow, we decide, the water will lower and well

walk home. We expect power will start coming

on in a week or so.There are many relaxed and friendly conversations,

especially on the roof. With all of the lights in the

city out, the night sky is beautiful. We lie on our

backs and watch shooting stars.Tuesday, August 30

We wake up to discover that the water level has risen

several feet. Panic begins to set in among

some. We inventory our food and find that, if we

ration it tightly, we have enough for five days. As

we discuss it, we repeatedly say, not that well be

here that long, but if we had to...We continue to explore the area by boat, helping

people when possible. The atmosphere outside is

a sort of post-apocalyptic, threatening world of

obscure danger, where the streets are empty and the

future seems cloudy. The water is a repellent mix of

sewage, gas, oil, trash and worse.We meet some of our neighbors. Most of the building

is empty. Of at least 250 apartments, there are

maybe 200 people in the building, about half white and

half Black. Many people, like us, are crowded 7 or 10

to an apartment. Like us, many people came here for

safety from the storm. Some have no food and water.

A few folks break open the building candy machine and

distribute the contents. We talk about breaking into

the cafe attached to the building and distributing the

food.We turn on a battery-powered tv and radio, and then

turn it off in disgust. No solid information, just

rumor and conjecture and fear. Throughout this time,

there is no reliable source of information,

compounding and multiplying the crisis.The reporters and politicians talk 80% about looting

and 20% about flooding. I cant understand how

anyone could blame someone for looting when they

just had their home destroyed by the neglect

and corruption of a country that doesnt care about

them and never did.Tomorrow, the news announces, the water level will

continue to rise, perhaps 12-15 feet. Governor

Blanco calls for a day of prayer.Wednesday, August 31

White people in the building start whispering about

their fears of them. One woman complains of

people in the building from the projects and hoarding

food. There is talk of gangs in the streets,

shooting, robbing, and lawless anarchy. I feel like

there is a struggle in peoples minds between

compassion and panic, between empathy and fear.However, we witness many folks traveling around in

boats, bringing food or giving lifts or sharing

information.But the overwhelming atmosphere is one of fear. People

fear they wont be able to leave, they fear

disease, hunger, and crime. There is talk of a

soldier shot in the head by looters, of bodies

floating in the ninth ward, flooding in Charity

Hospital, and huge masses (including police) emptying

WalMart and the electronic stores on Canal street.

There are fires visible in the distance. A

particularly large fire seems to be nearby - we think

its at the projects at Orleans and Claiborne.

Helicopters drop army MREs (Meal Ready to Eat) and

water, and people rush forward to grab as many as

they can.After the third air drop, people in the building start

organizing a distribution system.Across the street is a spot of land, and helicopters

begin landing there and loading people aboard.

Hundreds of people from the nearby hospital make their

way there, many wearing only flimsy gowns, waiting in

the sun. As more helicopters come, people start

arriving from every direction, straggling in, swimming

or coming by boat.A helicopter hovers over our roof, and a soldier comes

down and announces that tomorrow everyone in the

building will be evacuated.Across the street, at least two hundred people spend

the night huddled on a tiny patch of land, waiting for

evacuation.Thursday, September 1

People in the building want out. They are lining up

on the roof to be picked up by helicopters - three

copters come early in the morning and take a total of

nine people. Seventy-five people spend the

next several hours waiting on the roof, but no more

come.Down in the parking garage, flooded with sewage, a

steady stream of boats takes people to various

locations, mostly to a nearby helicopter pickup point.We hear stories of hundreds of people waiting for

evacuation nearby at Xavier University, a

historically Black college, and at other locations.Our group fractures, people leaving at various times.

Two of us take a boat to a helicopter to a refugee

camp. If you ever wondered if the US government

would treat US refugees the same way they treat

Haitian refugees or Somali refugees, the answer is,

yes, if those refugees are poor, black, and from the

South.The individual soldiers and police are friendly and

polite - at least to me - but nobody seems to know

what's going on. As wave after wave of refugees

arrives, they are ushered behind the barricades

onto mud and dirt and sewage, while heavily armed

soldiers look on.Many people sit on the side, not even trying to get on

a bus. Children, people in wheelchairs, and everyone

else sit in the sun by the side of the highway.Everyone has a story to tell, of a home destroyed, of

swimming across town, of bodies and fights and

gunshots and looting and fear. The worst stories come

from the Superdome. I speak to one young man who

describes having to escape and swim up to midcity.Im reminded of a moment I read about in the book

Rising Tide, about the Mississippi river flood of

1927. After the 1927 evacuation, a boatload of poor

black refugees is refused permission to get on

land until they sing negro spirituals. As a bus

arrives and a mass swarms forward and state police

and national guard do nothing to help, I feel like Im

witnessing the modern equivalent of this dehumanizing

spectacle.More refugees are arriving than are leaving. Three of

us walk out of the camp, considering trying to

hitchhike a ride from relief workers or press. We get

a ride from an Australian tv team who drive us to

Baton Rouge where we sit on the street and wait until

a relative arrives and gives us a ride to Houston.While we sit on the street, everyone we meet is a

refugee from somewhere - Bay St Louis, Gulfport,

Slidell, Covington. Its after midnight, but the roads

are crowded. Everyone is going somewhere.Friday, September 2

In Houston, I cant sleep, although we drove through

the night. Governor Blanco announces that

shes sending in more national guard troops, These

troops are fresh back from Iraq, well trained,

experienced, battle tested and under my orders to

restore order in the streets. They have M-16s and

they are locked and loaded. These troops know how

to shoot and kill and they are more than willing

to do so if necessary and I expect they will.

[WHAT TO DO]

Many people have called and written to ask what they

can do. I dont really have answers. Im still

tired and angry and I dont know if my home survived.But, here's some thoughts:

1) Hold the politicians accountable. Hold the media

accountable. Defend Kanye West.2) Support grassroots aid. A friend has compiled a

list at http://www.sparkplugfoundation.org/

katrinarelief.html3) Volunteer. The following is a call for volunteers

from Families and friends of Louisianas

Incarcerated Children, an excellent grassroots group:

Come and help us walk through the shelters,

find people, help folks apply for FEMA assistance,

figure out what needs they have, match folks up

with other members willing to take people in. We

especially need Black folks to help us as the racial

divide between relief workers and evacuees is stark.

Email us ASAP if you would like to help with this

work.[email protected],

[email protected]

[email protected]

[email protected]4) Organize in your own community.

5) Add your apartment to the housing board at

www.hurricanehousing.org.6) Support grassroots, community control of

redevelopment.Dont let New Orleans die.

More on Katrina, from independent sources, can be found on Znet.

[images from the Los Angeles Times, the first by LAT photographer Carolyn Cole, the second by the AP's Eric Gay]

Jordan has been an organizer for the International Solidarity Movement in NYC, and has himself spent time on the West Bank (occupied Palestine) and Gaza. If memory serves me right, he moved down to New Orleans about two year ago. He is currently an editor with left turn magazine. He has a calm demeanor and has struck me on the few occasions I've seen him speak as a really nice guy. He is definitely a community role model.