Nicolás Dumit Estévez and his performance piece, his art, was assaulted by New York City Police on Valentine's Day. They succeeded in shutting down his activities for the day, but the artist and the work somehow survives. Here he describes the project which he began and which the police concluded. The art survived the experience, and was made more powerful for having been so outrageously challenged, but the honor of our Police Department was again compromised, and in the same degree.

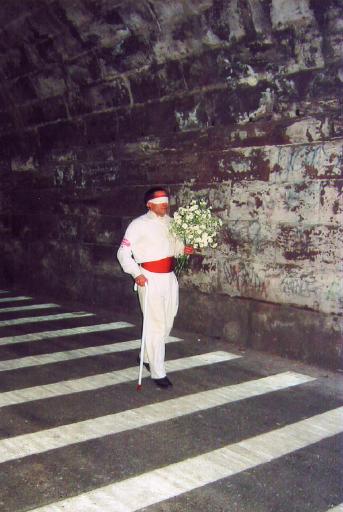

NOTES ON "LOVE IS BLIND" An intervention developed by Nicolás Dumit Estévez and modified by the New York City PoliceOn February 14 I left El Museo del Barrio blindfolded, unaware of what I would see at the end of a performance piece that I called "Love is Blind," which was part of "The Love a Commuter Project." This project consists of a series of site-specific performances and interventions that take place every year on Valentine's day in the New York City subway system. In 2003 the project was presented in conjunction with "The S Files" at El Museo del Barrio. Besides watching out for some icy spots on the sidewalk, my job during the performance was to locate pedestrians who would help me find the way to the subway station at 110th and Lexington Avenue in exchange for a white carnation. The plan was to save the remaining part of the bouquet to share with subway commuters. Along the way to the subway station a policewoman helped me cross under the tunnel below the train tracks on Park Avenue, and an older woman who spoke Spanish proffered a blessing "Dios te bendiga mi hijo," after making sure I was going to be ok. Someone who I perceived as a strong man grabbed me by the arm to help me walk from 108th to 109th Street, while a disgruntled pedestrian tried to confuse me when I asked him for directions. "You're at 125th St.," he said, while my Samaritan told me that we were crossing 108th. Another man helped me make it all the way down the stairs of the subway station. I remember feeling his hand as he took mine and guided it to the cold metal railing. I then proceeded to use the white cane I was carrying to search for an empty spot near the token booth. I found one on the north side of the station. Two children initiated the first underground interaction as they detached several carnations from the bouquet. "Take another one for your mother," yelled a commuter, perhaps from the other side of the turnstile. "Don't touch them," said an adult to a child who insisted on having one of the carnations. What felt to me like a rushing commuter snapped up a flower without giving me time readjust the bouquet in my hand. Then there were the predictable quiet moments between the departure and arrival of the Number 6 train. All of the sudden, the hissing sound of police walkie-talkies invaded the space. That day the city was under Code Orange, raised from Yellow by the Department of Homeland Security. Sensing what might be happening, I took the blindfold off and walked above ground to find that three uniformed officers were questioning my colleague Manuel Acevedo, who was videotaping the project, as well as a friend who came to watch the piece. After several attempts to explain what we were doing, we were ushered into the back of a car and driven to the precinct, where I managed to make a quick phone call from my cell phone before one of the agents confiscated my phone and Manuel's video camera. We were not permitted to contact anyone else. At the precinct I glanced at a booklet on fighting terrorism and the snapshots of several individuals who were wanted by the Law. We had plenty of time to kill as the agents busied themselves swiping our ID cards and figuring out what was recorded on the video camera they could not manage to operate. About 40 minutes later, an officer came to us and asked us to show him the video. He later return with our IDs, shook our hands and apologized. We could go. I remember shaking his hand while holding the bouquet in my other hand, when suddenly the friend who came to watch the piece took the flowers and tossed them into the trash, perhaps trying to rid himself of the memories of the incident. I rushed to retrieve them. The carnations still looked fresh, ready for other commuters to pluck them from the foam that held them in place. Instead, they ended up in a glass vase at home, as a reminder of how current law enforcement in the name of "safety" has reconfigured the use of the spaces we share in the city, not to mention the interactions we forge with one another in these so-called public places.

Nicolás Dumit Estévez

February 21, 2003, New York City

Amigo, estupenda manera de decir que la exclusión no es gesto inherente de nosotros los humanos y menos en nombre de una supuesta seguriad colectiva.