Some people would like us to think that it's all about the literature of literature, but the rest of us would probably rather read books than reviews, even if (or apparently for some, especially if) the pen is wielded by Dale Peck.

Actually I don't even like to go to readings unless the book is the work of a friend, or someone who is as brilliant and provocative as, say, Gore Vidal - or Dale Peck. But here's a recommendation.

Dale is a friend, but he's also a great artist who never lets his readers get too comfortable, so I'm going to be at the Chelsea Barnes & Noble next Thursday at 7 o'clock expecting to be both patted and scratched.

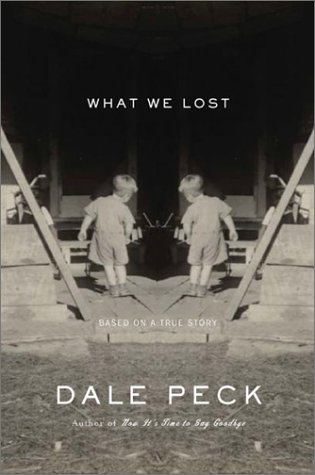

He wrote today, "please come hear me read from 'What We Lost', my new memoir (or, as the Times Magazine would have it, novel)". With that reference and a look at the James Atlas piece itself you can see that, although I believe the book hasn't yet been reviewed outside of the trade publications, the dustup has already begun.

The NYTimes site includes an excerpt of the "memoir", of which this is itself an excerpt:

He must fall asleep then because when he opens his eyes the truck is stopped and the old man is not in the cab. He assumes they've stopped for gas until he sees a gnarled branch above the windshield like a jab of brown lightning and he sits up. To his right a row of leafless trees stretches up the side of a hill and to his left there is a white house, small and rectangular, its tiny second-story windows the shape of dominoes laid on their sides. Before he gets out of the cab he grabs the pillowcase containing his brothers' clothes and the old man's medicine, and the first thing he does is fall flat on his face because he can't feel his feet. Still half asleep, he sits on the crust of snow that covers the ground like stale cake frosting and takes off Jimmy's shoes. The ground is cold and hard beneath his bottom but the bottoms of his feet feel nothing at all, and, teetering, rudderless, he stands up and floats around the truck in his socks, the pillowcase less ballast than slack sail hanging down his back. A pitted two-track driveway runs around the house and up the hill toward a pair of barns and a tall round building that the boy recognizes instinctively as a silo even though it reminds him of a castle tower. At the foot of the silo he sees the old man talking to another man. Like the old man, this stranger is short and thin and has only half a dozen strands of hair slicked flat to his skull, but unlike the old man he stands absolutely still, one hand holding a pitchfork lightly but firmly, tines down, and a cap on the ground between the two men, bottom up like a busker's. The only thing that moves is his head, which shakes every once in a while, back and forth: no. The old man's legs are wobbling and his arms are flapping in the air, and as he wobbles toward them the boy is reminded of a seagull he saw once in the bay. The seagull's legs were trapped in a fishing net, and every time it flapped its wings its orange legs would lift out of the water trailing weed-draped mesh. Over and over the bird's legs had shaken like the old man's with its efforts to free itself but each time, exhausted, it splashed down again.The old man and the stranger are still a good twenty yards away when the old man turns and reels toward the boy. His legs and arms make motions like the spokes of a rimless wheel, and he is shouting,

I won't let her send him away! Not my boy! Not my firstborn son! Not again!

He jerks right past the boy without seeming to see him, his doddering gait half step and half slide on the slick grade, and it seems pure chance that one of his flailing hands catches hold of the door handle, a veritable miracle that he is able to crack it open. The shotgun sound is like an echo of itself in the quiet air, and the boy whips his head from side to side as if he can find the original source. He is in the back of the house now. From this angle he sees that it is actually L-shaped. He can't see the farmhouse across the street, the mountain twenty miles to the south. He sees only a bulbous clump of gray-green evergreens and the tin-domed silo and the two barns and a patch of leafless woods at the top of the hill and then a big field studded with black-and-white and butter-brown cows. When the truck coughs into life one of the cows looks up from whatever thin strands it is pulling from the ground, looks first at the truck and then at the boy and then drops its head again and roots around for more grassgreen grass, the boy can see, even from this distance. It is the middle of January and thin streaks of snow paint zebra stripes on soil hard as a city sidewalk, but the grass that grows from that soil is still green, and by the time the boy turns back to the truck it has backed out of the driveway, narrowly missing what looks like a fencepost with some kind of placard mounted atop it. The truck would have gone into the ditch on the far side of the road had there not been a tree there. Instead something glass breaks, a taillight that is not already broken perhaps, and when the old man shifts into first the boy hears first the transmission's grind and then the glass as it falls onto the road. The truck goes so slowly that had he wanted to the boy could have run after it, could probably have caught it even, even with his numb feet. But he just stands there swaying, watching the truck recede as if one of them, the truck or the boy, is on an ice floe borne away from the shore by a half-frozen current. By the time the truck disappears over the hill the stranger has walked down from the barns and walked on by. There is smoke coming from a chimney on the left wall of the house and the stranger's pitchfork makes a metallic ping each time it strikes the frozen ground.

Feeling floods into the boy's feet then, as if a pot of pasta water had tipped off the stove and spilled over them. He reels, bites back a cry of pain; catches his breath and catches his balance.

Uncle Wallace? he says to the thin brown back retreating down the hill.

The stranger doesn't stop, doesn't turn around.

Get my hat, Dale, he says. At the door he pauses to look the boy up and down, and then he shakes his head one more time. In the failing light his scalp looks white and cold.

Don't forget your shoes, he says, and walks into the house.

For Dale's friends, fans, and the disgruntled too I suppose, the details for this reading and others scheduled across the country in the months ahead are these:

Wednesday, October 6 @ 7

Barnes and Noble Chelsea

675 Sixth Avenue, between 21st and 22nd

New YorkMonday November 10 @ 6:30

Free Library of Philadelphia, Independence Branch

PhiladelphiaTuesday, November 11 @ 7

Olsson's Dupont Circle

Washington, DCTuesday, November 18 @ 7:30

Wordsworth Bookstore

Cambridge, MATuesday, January 6 @ 7

Barbara's Bookstore

ChicagoThursday, January 8 @ 7

Bound to be Read

MinneapolisTuesday, January 13 @ 7:30

Cover Bookstore

(Cherry Creek location)

DenverSaturday, January 17 @ 3

Elliot Bay

SeattleMonday, January 19 @ 7:30

Annie Bloom's Bookstore

Portland, OregonThursday, January 22 @ 7

A Clean, Well-Lighted Place for Books

San FranciscoSunday, January 25 @ 5

Obelisk Bookstore

San DiegoTuesday, January 27 @ 7:30

B&N (West Pico location)

Los AngelesFriday, January 30 @ 7

Book People

AustinTuesday, February 3 @ 7

Rainy Day Books

Kansas City

Gawker has a very interesting interview with Dale:

http://www.gawker.com/archives/009725.php

It's bizarre to read something that smart on Gawker.

I think he and Choire are roommates?

Dale rules!

And, go Gawker!