[of a kind of harmony]

and I'm also very fond of red, when it's used well [scene from "Shadowtime"]

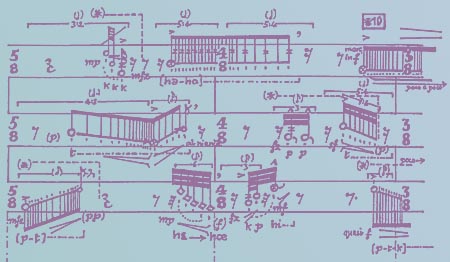

Brian Ferneyhough Time and Motion Study III 1974 16 mixed voices, percussion, live electronics [detail of the score]

I had intended to get tickets to Brian Ferneyhough's new opera, "Shadowtime," which receives its American premier next week, from the moment I had heard about it. But the Lincoln Center Festival flier we had received weeks ago had very soon been buried underneath competing mailings and was almost immediately forgotten - until this afternoon, when I read Jeremy Eichler's piece, "A secular Messiah gets His own Opera," in the NYTimes Arts&Leisure section. I immediately looked for the Festival site on line and then grabbed the phone, fearing that there might no longer be anything available but my best chance would be with a human voice. Then even as I was doing this I had to remind myself that this was not "La Boheme." The world wasn't going to be beating a path to Columbus Circle in order to hear an opera about "an arcane cultural philosopher" featuring "fantastically intricate music, with nothing as old-fashioned as a tune in sight," in Eichler's words - even if I had been seduced immediately.

While the two paragraphs from near the conclusion of the Times piece I'm copying below may not entirely explain my own love of difficult music (which is as much about the vulgar appeal of its invention, its energy, its novelty and its provocation as it is about its intellectual virtues), they do say something about the social and political utility of difficult art - in any medium.

"Shadowtime" had its premiere last year at the Munich Biennale, and critical reaction ranged widely. The Süddeutsche Zeitung hailed it as "an apex of modern operatic artistry," but The Sunday Times of London described it as overly cerebral, "an abstract idea of an opera rather than the thing itself." The truth may well depend on one's definition of modern opera.Oh yes, I had no trouble getting two good seats on the aisle in the orchestra, and for a fraction of the price of seats at that older and much more famous opera venue where they don't seem to be able to get past "La Boheme."Mr. Bernstein [Charles Bernstein, the librettist], for his part, readily concedes the many difficulties of "Shadowtime," and argues that they arise not only by design but by necessity. "Clarity is valuable in many situations, but not necessarily in art," he said in a recent interview at his Manhattan apartment. "Many will no doubt be befuddled, just as a work that seeks to be clear risks boring people. These are the risks you have to take."

Yet more seems to be at stake than simply keeping an audience challenged. When pressed, Mr. Bernstein echoes Benjamin's friend and colleague Theodor Adorno, who defended difficult music as having its own social value precisely because it teaches us how to withhold understanding and therefore helps us resist the allure of false clarity in the world beyond the concert hall. Complexity, in other words, is a worthy ideal in art because reality is even more complex and dissonant than the thorniest work of modernism, even if politicians and the commercial culture reassure us that everything is simple, clear and harmonious.

[first image from the NYTimes; second image from tagederneuenchormusik]

So did you like it? I just got home & was searching the web for comments & found your mention. I thought the music was great. But even though I have an enormous prejudice in favor of the "difficult," the libretto bothered me. It seemed to trivialize Benjamin (or at least it was unable to meet him on his level).