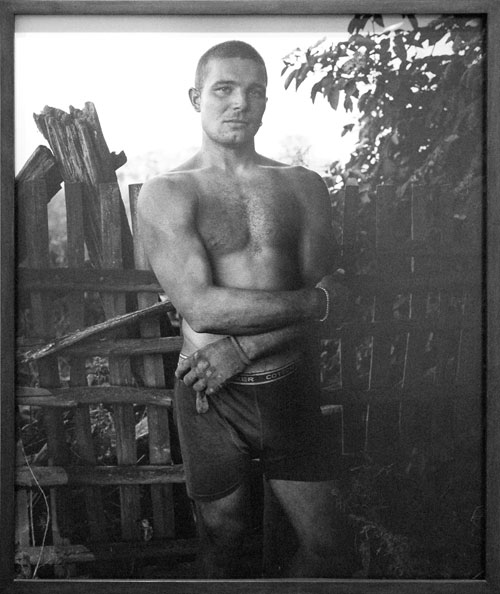

Ingar Krauss Untitled (Beelitz) 2006 gelatin silver print 40"x 33" [installation view]

Every year thousands of harvest hands come and go like birds of passage.*

Indulge me on this one, as I really wanted to upload this image. No, on second thought, I'd rather bring you with me, and try to explain why I'm so taken with it and all the the others in Ingar Krauss's current show at Marvelli Gallery, titled "Birds of Passage".

Yes, the man is beautiful. In fact he's very sexy. The very direct, black and white photograph looks like it has the special legitimacy this medium sometimes acquires with age, although the modern knit boxers reveal that the artist is not trying to deceive us on that account.

But there is much more to see here than the man's own sad beauty and the beauty of the Brandenburg landscape which Krauss has gently draped around his shoulders and around those of most of the other eight men in these portraits. Every one of his workers, photographed here at the end of a long day, is distinctly beautiful. The range of their ages spans every one of the decades in which a fortunate man might expect to enjoy robust life, although several of them would not normally be described as particularly sturdy.

The gallery's notes tell us that women, and sometimes entire families, are also a part of this seasonal worker migration, but here we see only men, and I suspect that males overwhelmingly dominate the numbers of these seasonal hands. Even the sad subjects of Dorothea Lange's documents weren't usually fighting to survive alone in a foreign land.

Krauss makes me envious of the Germans, and happy for their guests. We need the artistry of a Krauss or a Lange here in the U.S. today, to show us the guest workers on whom we depend so much, visitors both documented and not. This show is a reminder of how much could be done, and what it might mean to us all.

Neither the aesthetic nor the storytelling in work like this can be isolated from the complex history and the simple beauty of the specific environment in which these pictures were captured, in Krauss's case the underpopulated farms of the former Democratic Republic of Germany, or DDR. It's also hard to ignore the combinations of personal tragedies and personal hopes contained in the situations in which these migrant Eastern European farm laborers have placed themselves.

There is also tragedy on a larger scale, but a larger hope as well. Even to someone like myself, with a long experience of Germans and Germany, these people look very German. I think about that because it's likely that no one they are near thinks of them in that way. I'm pretty sure they wouldn't think of themselves in that way either. And yet here they're laboring in Germany for long hours on someone else's land in an alien environment, struggling with an overseer's foreign tongue in large richly-tilled fields which were once held in common by the socialist brothers and sisters of their own Polish, Russian, Ukrainian or other communities. Will they become Germans some day, or become the proud and prosperous brothers and sisters of Germans, as part of a larger, flourishing European community?

Well, I just wanted to say that I found it pretty tough to walk away from this show, both literally and figuratively. Thus this post.

The show has now been extended until February 2.

Oh, I almost forgot. I've seen and admired Krauss's work at least once before, in a stunning, but heartbreaking show, "In a Russian Juvenile Prison", mounted in the same gallery in October, 2004.

For more on the current show, see Vince Aletti writing in The New Yorker.

*

from the gallery press release