(he's been split up, and works a little more subtly today)

I was originally just going to make this a comment on an earlier post of mine, but when I realized that if I did so I'd be directly following one of my own I decided to make it a post instead. Besides, this gives it much more visibility, and I suspect what I learned last night will be news to many.

When I saw this statement inside an on-line NYTimes story last night I couldn't help thinking of a comment from one of my readers to the post in which I touched on the peculiarities of what we choose to call our democratic way:

In the overall race for the nomination, [after the New Hampshire primary] Clinton leads with 187 delegates, including separately chosen party and elected officials known as superdelegates. She is followed by Obama with 89 delegates and Edwards with 50."Superdelegates"? By my accounting, Obama should still be ahead of Clinton, having clearly exceeded her number of delegates in Iowa. I quickly checked my handy Wikipedia, and found that the system which established superdelegates was a response to a 1970's change in the Democratic Party nomination process. Control had been taken out of the hands of party officials and entrusted to the more democratic (small "d") primary and caucus formats, but the traditional smoke-filled rooms survived, albeit in diminished form. The bosses quicky arranged for the creation of a class of delegates to the presidential nominating convention, made up of elected officeholders and party officials, which was not to be bound by the democratic decisions made by primaries or public caucuses. Superdelegates comprise approximately one fifth of the delegates/votes in the national convention.

My commenter of last week argues for the democratic virtues of the American system, saying that in the "European system", rather than go through what I might represent as an absurdly drawn-out presidential campaign and a motley series of public primaries,

The parties decide internally who will fill posts, and these decisions are made outside of the process of the election cycle, which is why the cycle runs only 6 weeks. They spend much longer posturing internally, outside of the public eye. Does that sound more democratic?I would answer that the comparison isn't so simple as that which he outlines, and considering the incredible mess we have made of the tools of democracy which we have inherited, he may even be asking the wrong question.

There are many more important reasons why the American electoral system fails the democratic test, so I won't make too much of the impact of superdelegates, but being aware at least of their existence is one more small step toward dismantling the edifice of an unbearably selfish and destructive American exceptionalism.

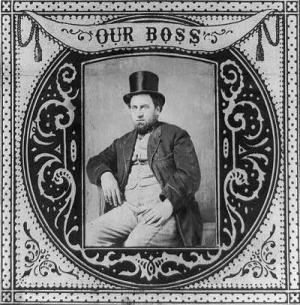

[image of Boss Tweed, on an 1869 tobacco label, from Wikipedia]

I think you're being too hard on the American system. The opaqueness of European and Canadian systems, where elites decide internally, are not much better.

Also, I particularly like U.S. primaries because it informs me about parts of the country (Iowa, NH, etc.) that I don't normally think about and makes me aware of some of the issues important to them.

I find it ludicrous that we allow two of the whitest, most rural states in the country to winnow our choices in the first month of primaries, to say nothing of the fact that the media treats anyone without at least $20 million in the bank as a "fringe" candidate.

The people put up as candidates prior to the primaries aren't chosen by any of us; the decisions which secured their positioning and their backing are no more transparent or democratic than those which determine who will assume the leadership of a European political party.

Moreover, in our own election practice neither the competence nor the ideas of candidates who make their appearance in this way are ever really the subject of open, rational discussion (no thanks to our media either), making it virtually impossible for the rest of us to decide between campaigning personalities on the basis of anything but personalities. Worse yet, we find ourselves bombarded by discussions of hair styles, spouses sex and religions, and what the parties themselves fade into the background. At least European voters have traditionally had the significant advantage of being able to understand what their parties stand for.

On Hrag's second point, I wouldn't want to argue for the merits of our current primary system on the basis of its attraction as reality TV.