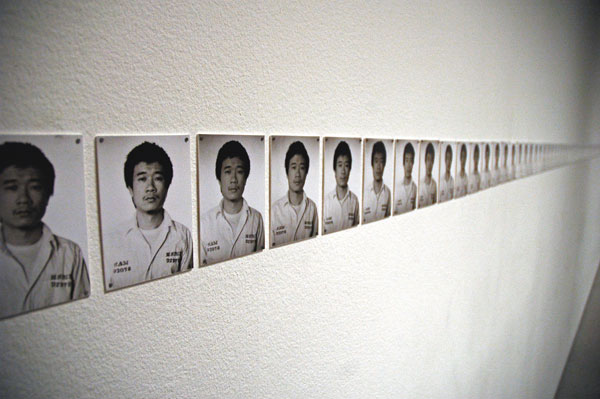

the artist's life becoming a concept [the wooden cell]

documented in time [the photographs taken daily]

I was ashamed that I hadn't immediately recognized who Tehching Hsieh was. That is, I had not only forgotten about his 1978-1979 "Cage Piece" but I had also, for the moment at least, not remembered the "time clock piece", "the outdoor piece" or "the rope piece", even though just the idea of these had thrilled me at the time, as I read about them in ordinary newspapers while living in Rhode Island before moving to New York.

After having breezed through Hsieh's exhibition at MoMA last Tuesday on our way to Klara Liden's piece in the next room (a first priority, because her piece had not yet been opened to the public), Barry and I were returning to check out his own, more sober installation, located just off Kippenberger's "Kafka's 'Amerika'" piece in the atrium. Museum Director Glenn Lowry had left the Liden room just before us, where I had heard him congratulating the curator for introducing such a terrific piece into the museum. He stopped to look at the Hsieh materials and documents and turned toward us as we entered the room apparently wanting to his clear enthusiasm for the work. [I love to see the guy at the top running around the big "shop" and sharing his excitement with visitors.] We agreed that it was an incredibly impressive and even astonishing project. I said that on registering it for the first time my second thought, and first question, had been, what does such a long experience of isolation from any outside stimulus do to your mind? I wondered aloud, what do you do after being alone with your mind for a year? I asked Lowry, do we know what he did later? He answered, "Apparently he didn't do much".

Which is both true and not quite so true, as I started to learn almost immediately after asking the question. Hsieh went on to commit himself to several more long-term performances equally as challenging, although not nearly so isolating as the first. But no, apparently until very recently no art was ever formally exhibited or sold. The last (latest?) two projects, the first a one-year assignment to "go in life", not seeing, making or talking about art, and a "13-years plan" to make art but not show it publicly, would each appear to have been a relative piece of cake, but together they seem to have meant the end of his art, at least by his own account, as documented inside a long and fascinating piece. "A caged Man Breaks Out at Last", by Deborah Sontag appearing in tomorrow's New York Times [slide show].

Tehching Hsieh tells us he is no longer an artist, but I think we can't take him at his word, and we must not, as I'll try to explain.

The work haunts me as I sit here trying to express something about the inexpressible. Alexandra Munroe, the senior curator of Asian art at the Guggenheim Museum, is quoted in Sontag's article, referring to Hsieh, "He is deeply philosophical". It seems to me he is something else: Hsieh is not a conceptual artist; rather, he has reduced his entire life to a concept. The work he has given to us seems to have come out of nowhere. It is so pure and sublime that it doesn't seem we could possibly deserve to be its legatees, especially since we've virtually ignored it for thirty years.