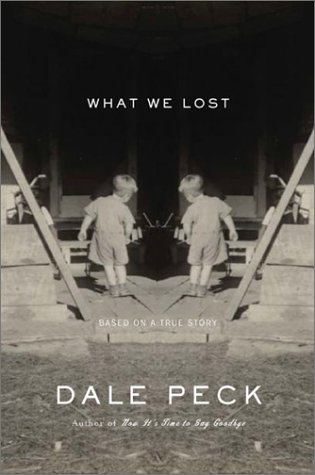

sounds of the city: part of the audience for John Cage's "Music for Carillon"

I love John Cage's music, always have, but even I understand that not all of it is lovable.

Late Sunday afternoon it was totally delightful. Sunday evening was a different story. The "Music for Carillon" which engaged much of Fifth Avenue at dusk reflected both the beauty of his art and the playfullness of the man. There was no way for devotees to avoid the ambient sounds of a busy city and there was no way the busy city (or at least that part of it) could avoid the musical occasion.

Best parts: the smiles, and watching the music engage and sometimes totally arrest passersby, especially children; oh, and listening to the counterpoint added by the beep beep beep of the front-end loader across the street.

The NYTimes reviewer referred to the "humming Cagean symphony of the street." I wonder if he had also been at Saturday afternoon's performance by Margaret Leng Tan of Cage's "Sonatas and Interludes for Prepared Piano".

That day's musical experience would have been perfection but for the regular interruption of rehearsal sounds and security guard radio conversations throughout. This time Zankel Hall's persistent subway sounds were totally overwhelmed by totally avoidable screw-ups. Ms. Tan briefly interrupted her performance early on and turned to the audience, smiling, to comment, "This is something of a Cagean moment." In spite of continual distractions, she went on to play magnificently for almost another hour. Unfortunately Cagean moments would not have been embraced even by Cage until the fifties, years after he had composed the delicate piece she was performing. Carnegie Hall owes her and the audience a formal apology.

Sunday night was . . . interesting. But for me, and also at least for the same Times reviewer, Jeremy Eichler, who had reported on the Carillon concert, it was a disappointment. Three extremely austere pieces were programmed for the evening, "Music for Three (by One)," excerpts from "James Joyce, Marcel Duchamp, Erik Satie: an Alphabet" and Cage's "Winter Music," was performed simultaneously with a solo vocal work from his "Song Books." Eichler laments:

More Cage followed that night at Zankel Hall, where 15 pianos were strewn across the stage and balconies, conjuring hopes of more exhilarating sonic anarchy, but alas it was not to be.Oh yes, these concerts were all part of the "When Morty Met John..." festival, of which the highlight was almost certainly Morton Feldman's Second Quartet. John Rockwell reviewed that performance, but he must have missed the "Sonatas and Interludes" excitement of that afternoon, because he praised Zankel Hall's "acoustically sealed" insulation and its impressive doors, writing that passing through them was "like entering a bank vault".. . . .

It was of course a musical lecture on Zen-like awareness and Cage's theories of silence, and there are profound truths here if one is in the right frame of mind to receive them. Some in the audience seemed up for the task, sitting with eyes closed in poised reflection. This listener was not among them. For about 15 minutes I admired Cage's refusal to compromise, but I found the mandated stillness to be heavy-handed. After that I just kept hearing the subways coming and going beneath Zankel Hall, and wished I were on one of them.

He praised the Flux Quartet for a remarkable performance, and he described the work itself as "an amazing composition one whose beauties (longeurs is a word that doesn't even apply) are still slowly revealing themselves, from performance to performance." [There have been exactly two since it was composed in 1983.]

The Quartet is approximately six hours in duration, so we will probably always have some wait between hearings, meaning there is at least little chance of tiring of it. I bought the CDs, so I guess that means I will enjoy testing that proposition.