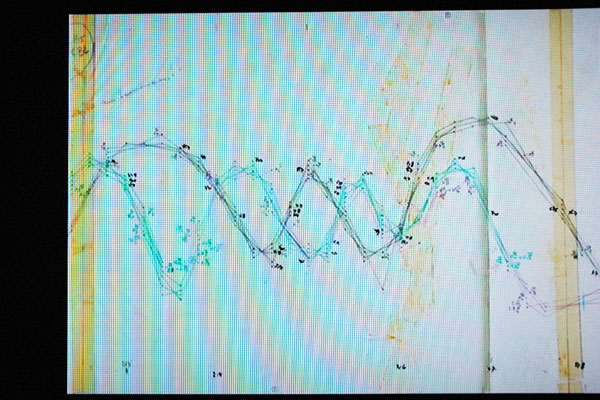

large detail of a still from a video of Iannis Xenakis' "Pithoprakta" (1956), which has the composer's sketches and renderings accompanying the piece itself [currently installed at the Drawing Center]

I love music, especially unfamiliar music, and since I've now been listening to the stuff for a good part of a century, that means my taste may not be shared with most people. The music of Iannis Xenakis (1922-2001) is a case in point, but judging from the fuss being made over this composer recently, and that without the excuse of a major anniversary, maybe I'm about to go mainstream for once.

It's been a couple months since I first decided to do a post about the wealth of opportunities we've been given lately to hear the Greek-born composer's powerful and very idiosyncratic music. It's now the middle of March and most of the concerts to which I'd been looking forward have already happened. I'm ashamed to admit I've only been to two. The first was “Xenakis & Japan”, at Judson Church February 28, an evening of music and dance devoted to the composer's interest in Japanese music and theater and presented by the Electronic Music Foundation.

I find it extremely difficult to write about music on this blog, even though all my life it's been at least as important to me as the visual arts, and probably more so. I've had no significant education in anything other than the liberal arts (which, contrary to what some think, actually do not actually include any form of "art"). I am able to write about the visual arts at least tentatively, from my position as an unlearned, passionate observer, and not least because I have the help of a camera. The performing arts however are a serious problem for me, since I am normally unable to photograph the art, and stock promotion photos which are seen over and over again bring nothing new to the subject. The performing arts are an incredible challenge.

In fact I had little excuse to miss the opportunity of writing a short bit about Xenakis, since here there was a real possibility of including images. I'm thinking of the beautiful studies with which the composer rendered his aural creations on paper (creations which he sometimes described with performances in light and space as well). Maybe only John Cage's own lyrical (yes, lyrical) drawings could match their output, their dynamism, and their beauty.

score for John Cage's "Chess Pieces" (1944)

There were some eight or so concerts of Xanakis' music listed on the press announcement released perhaps two months ago by the Drawing Center, and over the following weeks I learned about a number of others. We've now moved beyond all their dates, but the composer/architect/artist's sketches and renderings remain on view on Wooster Street (with pretty extensive musical accompaniment on headphones) through April 8th.

In the second recent concert I attended in which his music was programmed it seemed to have been designed to play a minor role, as surprising as that may seem to anyone acquainted with it. In a concert at the Paula Cooper Gallery on Tuesday evening Xenakis was only one of three contemporary composers featured and his contribution was both the shortest and the only one which did not require a dozen or more players.

In addition to the visual art she exhibits in her eponymous gallery, Paula Cooper has always hosted, in the description found on the gallery site, "concerts, music symposia, dance performances, book receptions, poetry readings, as well as art exhibitions and special events to benefit various national and community organizations". The page also reminds us that, "For 25 years until 2000, the gallery presented a much celebrated series of New Year’s Eve readings of Gertrude Stein’s 'The Making of Americans' and James Joyce’s 'Finnegans Wake.'”

I remember many of these occasions, including two important ACT UP fund-raising auctions Cooper hosted in 1990 and 1991, which were extremely important for AIDS activism, and for me.

Gertrude Stein came back to the the Paula Cooper Gallery this week, through a performance of Petr Kotik's "There is Singularly Nothing". The instrumental frame of the performance, by his own instrumental group, The Orchestra of the S.E.M. Ensemble, was an intensely-elegant affair. This roughly one-hour work, which incorporates a delicious text ["Composition as Explanation"] from Gertrude Stein, an American treasure, was first performed in the early seventies and re-invented, with different directives to the four singers, for the March 16 performance.

Collaborating with the SEM for the evening was the new-music concert series, Interpretations 21. A small vocal ensemble, augmented by Thomas Buckner and Gregory Purnhagen, who had solos in the Satoh piece, was shared by the two larger works.

The concert had begun with the world premier of Somei Satoh's "The Passion", an oratorial using an abbreviated version of the Christian biblical text described by the name. I cannot account for the choice of subject by a Japanese composer whose own experience and music are both actually founded in the philosophies of Shintism and Zen Buddhism. I did recognize some poetic allusion, although perhaps accidental, in the fact that the performance of this Passion took place in a room dominated by a full-size sculpture of the scaffold used to hang the workers known as the Chicago anarchists or "the Haymarket Martyrs" in 1887. The installation was created by Sam Durant, the artist currently being exhibited in the gallery, whose recent work work has dealt with capital punishment.

Xenakis' 1976 virtuoso piece, "Mikka 'S'", for solo violin, followed the Satoh piece. The performer, Conrad Harris, stood high above the audience, at one corner of the scaffold Durant intended, bare of all but its familiar water dispenser, to double in function as a worker’s break room.

A postscript, from the text of the Kotik piece, Gertrude Stein on "modern composition":

Those who are creating the modern composition authentically are naturally only of importance when they are dead because by that time the modern composition having become past is classified and the description of it is classical.

[image of Cage's notations from greg.org]