When I was very young and still a wide-eyed Midwesterner, I used to think that one of the neatest things about art was that you could conceivably do something that was more or less an accident, and pretty messy, or you might even find something somewhere that already existed, and you could put it into a frame or in a nice room and it would look very cool.

I loved Modernism, even as a child.

I skip ahead now, and I recall that for a number of years I've been watching more and more artists do stuff that didn't want to be in simple frames or placed in perfect white rooms, and in fact it was stuff that wouldn't look as cool if it were there.

I love messy art too.

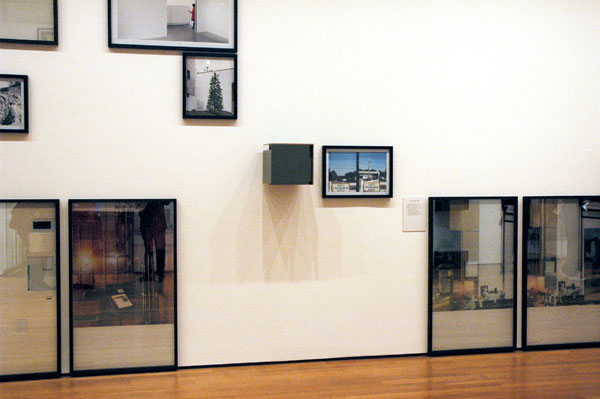

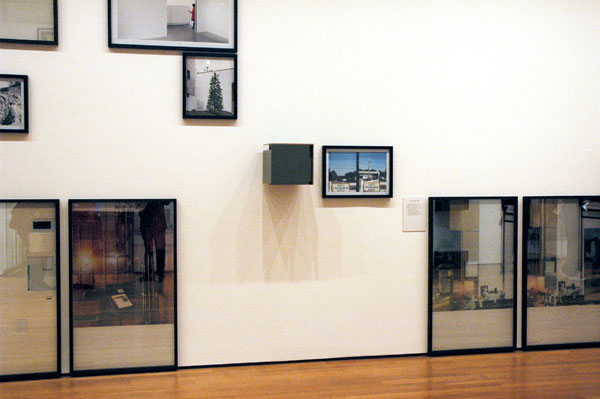

The artist Jan De Cock puts some very nice stuff in those frames and he installs those pictures and his very nice sculptures in those rooms. It works very well, and it looks really great. In fact it looks monumental. The Museum of Modern Art hosted a press preview last night for a very striking exhibition of De Cock's work, titled, as luck would have it, "Denkmal 11" [Monument 11].

It's so darn neat! I found myself instinctively resisting its pull, but I can't argue with what I have to describe as the artist's genius.

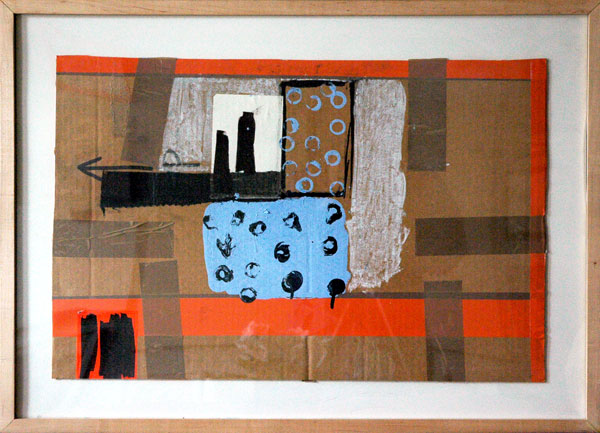

If I say that I think what he does could also work without the expensive constructions which delight the mind and eye here and in other installations, I'm not taking anything away from what he has accomplished. I can imagine his voice and his gaze opening us to just as much eloquence and beauty if he were content with humbler, materials mounted more humbly. While the sharp edges and perfect planes of the elegant Formica boxes which visually secure and give depth to the installation's two-dimensional works (hung so as to claim the full height of every wall) are clearly his choice, they could just as well be constructed of cardboard with a variety of cardboard mats substituted for the fine frames

But it certainly works as it is.

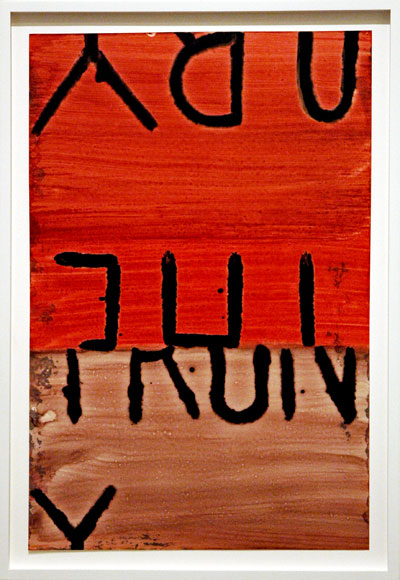

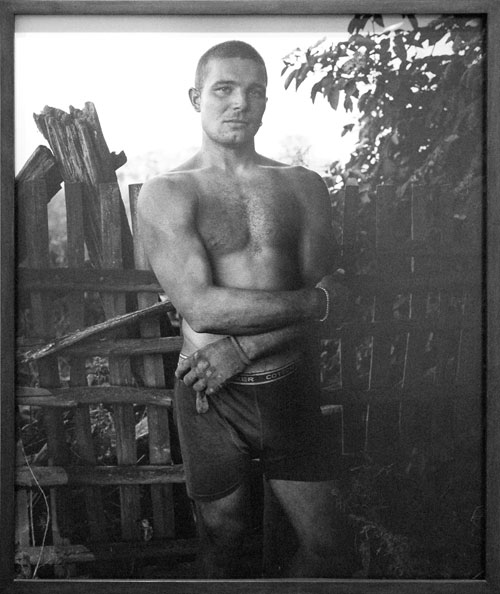

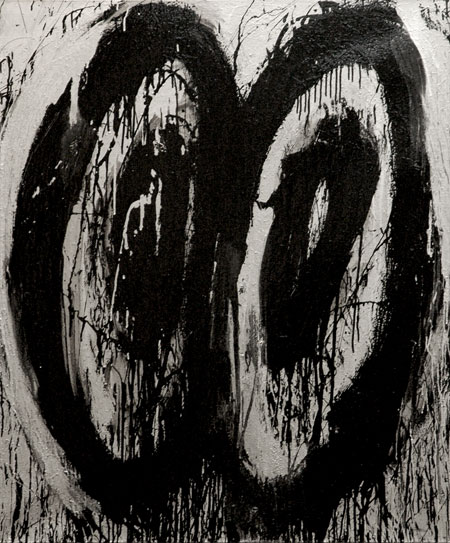

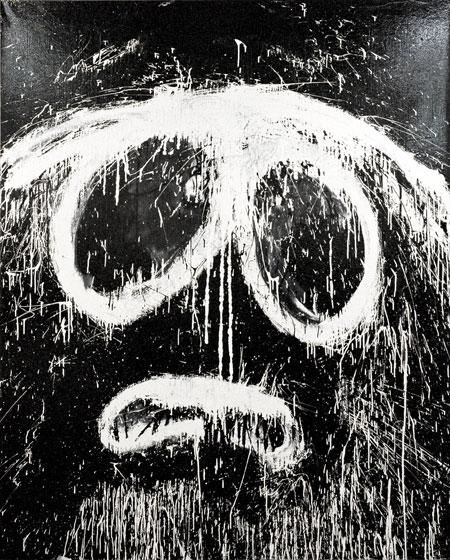

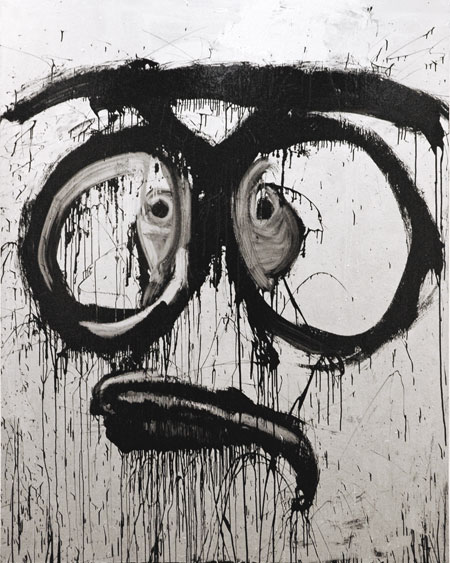

This is not "found art" as it is usually encountered today, but although what he employs in his work isn't physical detritus, it really is "scraps" of found and created images which describe a broad category of the "monuments" of our modern American condition. Like the work of his contemporaries who manipulate assembled elements, what makes it art is both what he picks and what he does with it after its picked. What makes it monumental is its encyclopedic ambition.

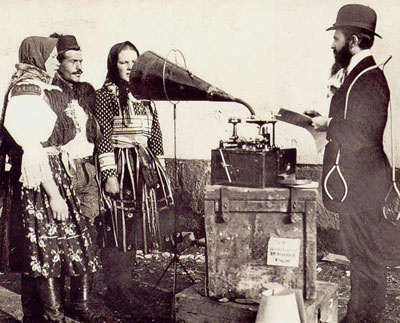

I've now encountered De Cock's art for a third time, even if this may be his first solo show in the U.S., so maybe I'm ahead of most of my compatriots who will find their way to the galleries at MoMA in the next three months. When I was invited to a private installation in March, 2006, I was little prepared for what I saw. I felt I had come into the middle of a conversation, but my curiosity was roused. A second encounter at an installation in Printed Matter's Art Book Fair that November reminded me that I had still not done any studying, but at least I finally met the artist - and I tried to cram the book.

The show at the museum looks terrific, and even if all you manage to get to before wandering through the clean white spaces is the writing on the outside wall, you should have enough of an idea of what it's about to enjoy what you see. Linger. Look closely at the images and the way they have been mounted, then peer at and into the sculptures and investigate the way the frames and boxes have been arranged.

You won't get bored. There's probably much more here than any of us will be able to see in the time we alot ourselves. Just as soon as I thought I had put some of this stuff together - brought it to where I thought I had figured out what he'd done - put it into my own frame - I found something that had totally escaped me until then and I wanted to point it out and talk to someone about it.

I brought home two things that might have made the show for me without any help from the art. The outside wall text asks, regarding De Cock's approach to image-making, "What is the most important thing that remains, the images or a way of looking?" A few minutes later Roxana Marcoci, the show's curator, spoke to the people assembled at the press preview tonight, saying something about the artist believing, as I very much do, that Modernism is the most important movement in the history of art, and (this is the most important part) that it did not end - that it will not end.

Now if we could only get our local institution to consider those two postulates. Photography prohibitions, to begin, would not survive such an examination, but nor would the current far-too-safe and sleepy curatorial practice. We see truly contemporary modern art too rarely in the Museum of Modern Art; we should all be able to take images of it, and of the rest of the archive, with us when we leave.

De Cock being interviewed by NewArtTV in the Bernd and Hilla Becher gallery next door

Jan De Cock and Roxana Marcoci